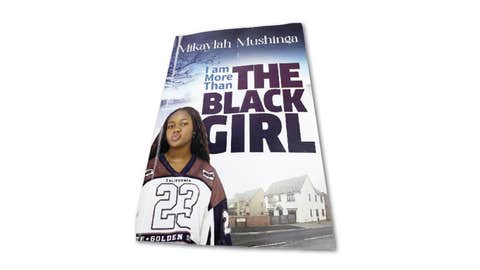

Teenage student Mikaylah Mushinga says she had to constantly explain to her schoolmates in England that Zimbabwe is a normal country with a lot of rich people who live luxurious lifestyles

*Teenage student Mikaylah Mushinga says she had to constantly explain to her schoolmates in England that Zimbabwe is a normal country with a lot of rich people who live luxurious lifestyles*

https://chat.whatsapp.com/IiQcAa8l9W1HfaZYYPy0mK

*TO ADVERTISE CALL/APP 0772964428*

The 13-year-old, who relocated to the UK with her family three years ago, has written a book titled ‘‘I’m More Than The Black Girl,’’ in which she chronicles the challenges she has faced in settling to life in England.

In Chapter 13, she writes about finding herself ‘‘Between Two Worlds.’’

“Back in Zimbabwe, there was no deep reflection about life, no second guessing, no weird glances in corridors, it was normal.

“I didn’t even need to write this book. But, in the UK, my whole identity became a conversation starter. It reminds me I’m not really from here. Not in their eyes.

“It doesn’t matter how I dress, how I speak or how many years I live here. To them, I’ll always be from somewhere else.

“I have to constantly explain that Zimbabwe is a normal country with lots of rich people who live in way more luxury.

“It’s exhausting having to defend your home, your people, your childhood — all because someone watched a charity advert once.”

She adds: “I used to try and hide the Zimbabwean in me. My accent changed so quickly — not because it had to but because I wanted it to. I wanted to blend in, I didn’t want to sound different.

“But now? I miss that accent. I miss sounding like where I came from. I miss feeling like I belonged somewhere completely, without having to split myself into two.

“Now, I switch between English and Shona without thinking. At home, it’s mostly Shona — mama says English makes her feel like she’s still at work. Daddy doesn’t really care, as long as we’re speaking.

“But, outside, speaking Shona feels risky. I remember scrolling on TikTok when some Karen started talking about how ‘nasty’ it is that we eat food with our hands, how it’s ‘so dirty.’

“I don’t understand why they can’t process the simple fact that we can wash our hands.”

At times, she says, the disappointment has come from being with fellow black people.

“Sometimes, I’m even around black British people and still feel left. Some of them were born here — they have the accent, the slang, the rhythm of this place.

“And me? I’m in between. Too English for the Zimbabweans, too Zimbabwean for the English. When I’m around white people, I notice everything — my hair, my skin, my slight accent.

“When I’m with black British people, I still don’t always fit. They know this place better than I ever could. Sometimes I feel I’m faking it in both worlds.

“When I stepped onto the plane, it’s like something stayed behind in Zimbabwe — pieces of me fading as the clouds covered Harare, my home.

“My parents don’t expect me to stay fully Zimbabwean. They understand. But sometimes they remind me, ‘in Zimbabwe we did . . .’

“I miss being black without having to explain it. Without the stares, the questions, the ignorance, just being, just existing in a space where I didn’t have to split my identity into digestible parts.”

She adds:

“Sometimes, I miss the simple things — going to Pick n Pay with Uncle Brighton for rice and chicken or mince, depending on the day. Visiting dad’s workplace to play on the laptops for hours chatting with his friends or looking at the whole city from the top of Herald House.

“Shopping at Sam Levy’s. Eating Chicken Inn or Pizza Inn’s chicken and mushroom pizza. It’s the simple things I didn’t even understand the value of back then.”

Mikaylah says her first initiation into British culture was tough, especially at her new school.

“They asked if I had water back home, if I lived in a hut, if I knew how to speak English, they laughed at where I come from, mocked the way my people lived and told me I was ‘whitewashed’ when I spoke too well.

“There were days I cried myself to sleep and the days I stood up and let my anger burn through the noise.

“I was the African girl, the girl who got jumped, the girl who refused to break inside.

“This is my story — of what it means to carry the weight of other people’s ignorance and still stand tall. Of finding family in the smallest kindness, strength in the sharpest pain and pride in the very thing they tried to shame.”